Radical Candor

Defining Management

At the beginning of the book, Kim Scott takes a stand at trying to define what management is. What is that managers/boss/leaders do?

They achieve these results not by doing all the work themselves but by guiding the people on their teams. Bosses guide a team to achieve results.

Kim Scott, Radical Candor

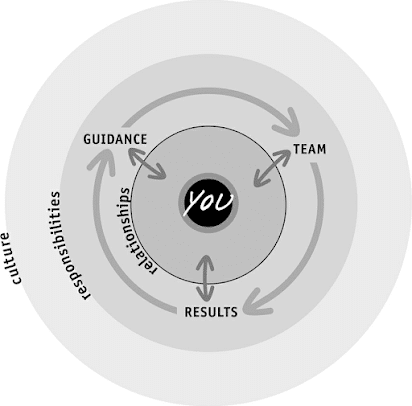

She identifies three areas of responsibility for managers:

- Guidance: often called feedback is expressed both in terms of praise and criticism.

- Team-building: which is about how to keep the team motivated, creating a balance between its components.

- Results: most apparent, it’s about to get things done.

Out of her experience, she also stresses the importance of relationships, as these are the key drivers for successful managers. These, together with your responsibilities as a manager and the culture of the organisation, create a virtuous cycle for management.

Fig.1: The Management Cycle. Source: Kim Scott, Radical Candor

Fig.1: The Management Cycle. Source: Kim Scott, Radical CandorFigure 1 shows the representation of this cycle. It’s easy to immediately see that things can go quickly wrong by simply unbalancing one of the elements of the model. Trust is the glue that keeps everything working at the level of relationship, and Candor is the main element to develop Trust.

What is Radical Candor?

Kim Scott builds a model to define what Radical Candor is. She starts by observing different ways of interacting and giving feedback and has developed a quick visual matrix that allows understanding the different styles. And she maps them on two axes that are 1) about Care Personally (which is how much you care about the relationship) and 2) about Challenge Directly, which goes around telling people when their job is good (or bad).

Fig.2: The Radical Candor Matrix. Source: Medium

Fig.2: The Radical Candor Matrix. Source: MediumThis matrix is not an assessment model. The author is clear in stating that we all might go through all 4 of the different styles sometimes also multiple times in the same day. The challenge is to go intentionally to the Radical Candor quadrant as much as possible for all the valuable relationships we have.

Obnoxious Aggression™ is what happens when you challenge but don’t care. It’s praise that doesn’t feel sincere or criticism that isn’t delivered kindly.

Ruinous Empathy™ is what happens when you care but don’t challenge. It’s praise that isn’t specific enough to help the person understand what was good or criticism that is sugar-coated and unclear.

Manipulative Insincerity™ is what happens when you neither care nor challenge. It’s praise that is non-specific and insincere or criticism that is neither clear nor kind.

Radical Candor™ is when you have a healthy mix of the two.

Consider this scenario to understand the differences between each type. Your co-worker’s fly is down.

- Obnoxious Aggression: (Shouts) “Look his fly is down!”

- Ruinous Empathy: (Silent, too worried about his feelings to say anything. It would embarrass you.)

- Manipulative Insincerity: (Silent, too worried about your own feelings to say anything. You want him to still like you.)

- Radical Candor: (Whisper) “Your fly is down.”

The radically candid approach is the most effective, right?

When you're radically candid, you provide the guidance your team needs to improve, both on a personal level and a professional level.

But it’s not easy.

I’m a true Texan, and grew up with the mantra, “If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all.” Kim Scott, however, disagrees.

“Now it’s your job to say it. And if you are a boss or a person in a position of some authority, it’s not just your job. It’s your moral obligation. Just say it!”

Being radically candid may mean what you say is not always nice, but it is the most kind, and that’s what you have to keep in mind.

Radical Candor is not a hierarchical attribute; it needs to be practised in all directions in organisations. It requires energy, which is why it should not be looked at constantly, but only when needed. And the secret to developing it, as a manager, is to ask for candid feedback first.

It’s easy to fall in the other quadrants, and I think we have all experienced managers and colleagues that quickly fall into one of the different three categories. I felt Ruinous Empathy to be the most interesting one when we think about the importance of the relationship. Still, we fail to challenge the other, which essentially means we don’t care about her/his development.

Rethinking Talent

Chapter 3 introduces a fascinating consideration about how to manage teams and addresses the mindset linked to traditional Nine Box based talent Management. The author pushes for managers to think in terms of the motivation of their teams, and not by applying simple maths. She challenges the concept of potential and prefers using growth instead.

Fig.3: Growth Management Matrix. Source: Kim Scott, Radical Candor

Fig.3: Growth Management Matrix. Source: Kim Scott, Radical CandorThe result is a matrix that takes into consideration personal preferences and motivation, and does not consider only the “high potential“. In this, she also introduces three management styles often appearing when talking of employee development: Absentee Manager, micromanager and Partner. Of course, the preference is for the last option.

When we think about the growth of our team, do we only reward those who want to go in management? Those who are super aggressive with their growth?

What about the team members who are content? Do we judge them for not growing fast enough?

We’ve been working on our career paths internally and this constantly comes up. On a more micro level, it comes up when we go into each one-on-one and discuss the future.

In Radical Candor, Kim Scott discusses the concept of Superstars vs. Rockstars. You need both in your company to be successful.

- Superstars: are change agents, ambitious at work, want new opportunities (note: not every Superstar wants to manage.)

- Rockstars: are a force for stability, ambitious outside of work or simply content in life, happy in their current role

Neither one is better than the other, and people can move between the two depending on what’s going on in their lives.

As a manager, it’s your role to learn what motivates each person on your team, “what their long-term ambitions are, and how their current circumstances fit into their motivations and life goals.”

When you understand that, and they know you do, you are able to be radically candid. They know you care personally.

Driving Performance

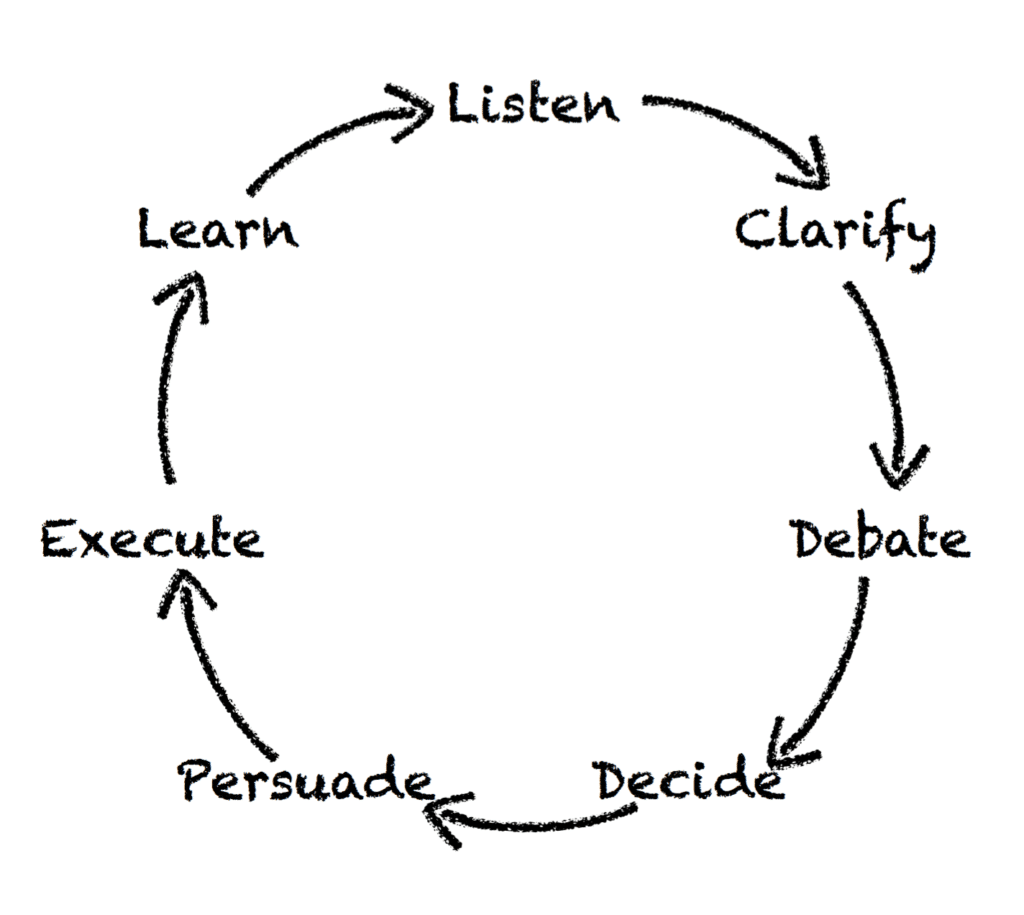

Chapter 4 focuses on how to drive performance. It is based on the assumption that telling people what to do doesn’t work. For this, she introduces what she defines at the Get Stuff Done Wheel. A 7 step iterative process that can support growth.

Fig. 4: Get Stuff Done Wheel. Source: Kim Scott, Radical Candor

Fig. 4: Get Stuff Done Wheel. Source: Kim Scott, Radical CandorFirst, you have to listen to the ideas that people on your team have and create a culture in which they listen to each other. Next, you have to create space in which ideas can be sharpened and clarified, to make sure these ideas don’t get crushed before everyone fully understands their potential usefulness. But just because an idea is easy to understand doesn’t mean it’s a good one. Next, you have to debate ideas and test them more rigorously. Then you need to decide—quickly, but not too quickly. Since not everyone will have been involved in the listen-clarify-debate-decide part of the cycle for every idea, the next step is to bring the broader team along. You have to persuade those who weren’t involved in a decision that it was a good one, so that everyone can execute it effectively. Then, having executed, you have to learn from the results, whether or not you did the right thing, and start the whole process over again.

It is interesting the parallel with a lot of the critical skills we have already seen: Listening, Curiosity, Learning Agility, Decision Making, Authenticity.